How a small North Carolina town and a Dutch monopoly expose the semiconductor industry’s hidden vulnerabilities

Technology & Geopolitics

Nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, the town of Spruce Pine seems an unlikely fulcrum on which the global technology industry balances. With a population of barely 2,200, it possesses none of the gleaming fabs of Taiwan or the research parks of Silicon Valley. Yet according to geopolitical experts and supply chain analysts, this unassuming Appalachian settlement controls something no amount of money can easily replicate: the world’s only commercially viable source of ultra-high-purity quartz.

The quartz deposits beneath Spruce Pine formed 380 million years ago when the African and North American tectonic plates collided. The extreme heat and absence of water during their formation created silicon dioxide of unparalleled purity – material so refined that it has become indispensable to semiconductor manufacturing. Two mining operations, owned by Belgium’s Sibelco and the Franco-Norwegian joint venture Quartz Corp, supply an estimated 70 to 90 per cent of the world’s high-purity quartz. Without it, the crucibles used to grow the silicon crystals that form the basis of every advanced microchip simply cannot be made.

“It is rare, unheard of almost, for a single site to control the global supply of a crucial material”

“It is rare, unheard of almost, for a single site to control the global supply of a crucial material,” writes Ed Conway in his book Material World. “Yet if you want to get high-purity quartz – the kind you need to make those crucibles without which you can’t make silicon wafers – it has to come from Spruce Pine.”

The vulnerability of this arrangement was laid bare in September 2024 when Hurricane Helene tore through western North Carolina. Both mining operations suspended production as the community struggled with catastrophic flooding, power outages and infrastructure damage. For several anxious weeks, semiconductor manufacturers from Taiwan to Texas monitored their crucible inventories and contemplated the unthinkable: a prolonged disruption that could ripple through every industry dependent on advanced chips.

The myth of Chinese dominance

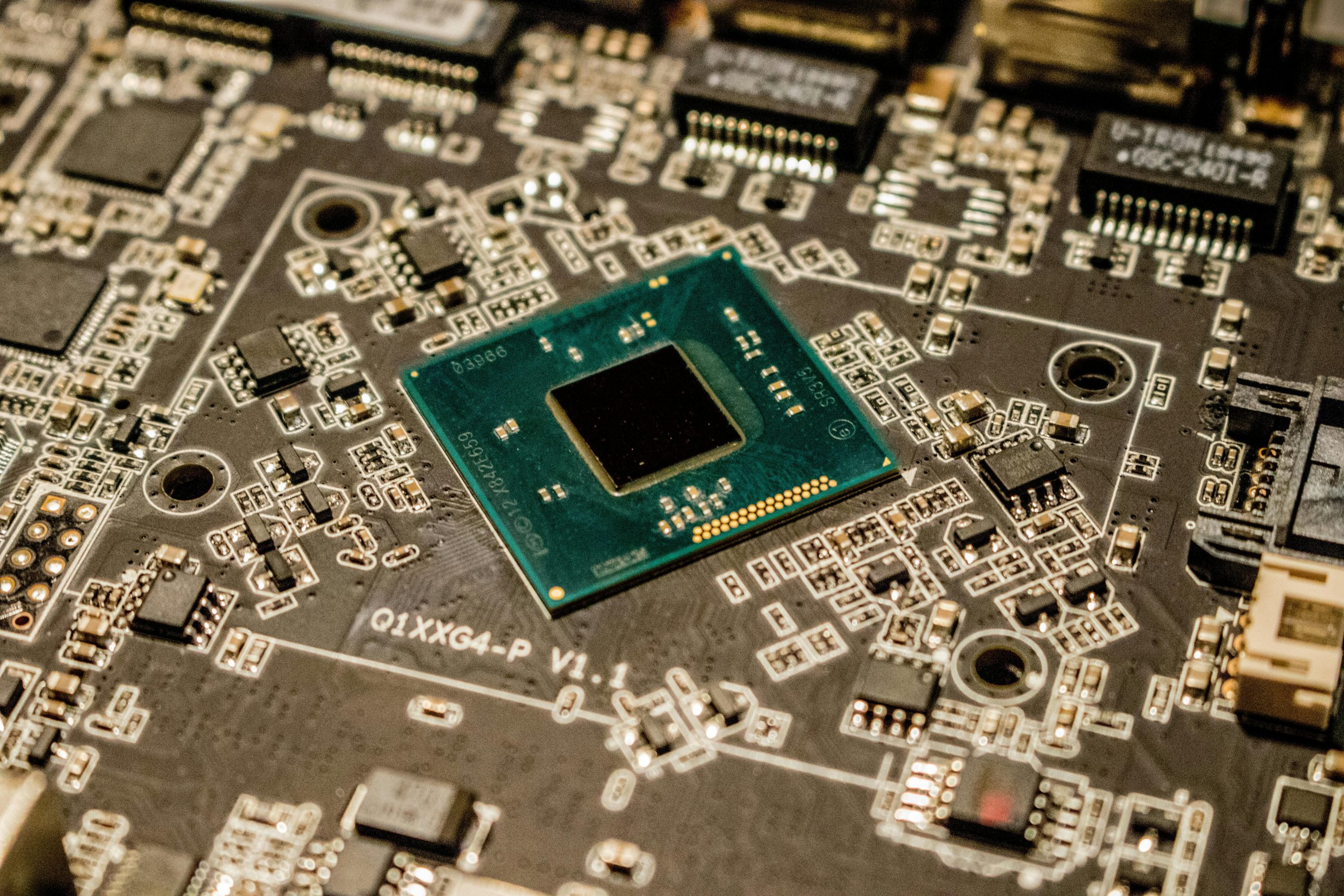

Spruce Pine represents just one node in an extraordinarily complex web. The semiconductor supply chain encompasses approximately 30,000 independent inputs and 100,000 discrete manufacturing steps. No single nation controls a majority share of any critical segment – a fact that cuts both ways in the escalating technology competition between the United States and China.

Much has been written about China’s dominance in processing critical minerals. Beijing controls 98 per cent of global gallium production, 70 per cent of indium and 60 per cent of germanium – elements essential for compound semiconductors used in everything from 5G infrastructure to defence systems. In December 2024, following expanded US export controls on chip technology, China effectively banned exports of gallium, germanium and antimony to the United States, closing loopholes that had previously allowed materials to reach American manufacturers via third countries.

Yet this dominance comes with a crucial caveat that is frequently overlooked. China’s processing capabilities, while extensive, do not extend to the ultra-high purity levels required for advanced semiconductor fabrication. The technical base remains, by most measures, that of a developing industrial economy when it comes to the most demanding purification processes.

Consider copper. Raw ore is extracted in Chile or Peru, then shipped to China for primary processing – removing all but roughly 2 per cent of contaminants. But for semiconductor applications, this is nowhere near sufficient. The material must then travel to facilities in the United States, Germany, Japan or South Korea, where it undergoes further refinement to achieve what industry insiders call “eight-nine” purity (99.999999 per cent) or beyond. At these levels, contamination measured in parts per billion can render a chip defective.

“You’re building incredibly complicated chips that have, in some cases, 100 billion transistors on a chip the size of your thumbnail,” explains Gregory Allen, director of the Wadhwani Centre for AI and Advanced Technologies at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies. “One atom being out of place could mean a defect that breaks the chip.”

The result is a supply chain that defies simple geopolitical narratives. Materials routinely cross borders multiple times during processing, with China often serving as an intermediate handler rather than a final arbiter. Chinese manufacturers must reimport the ultra-purified components that form the basis of their own semiconductor industry – a dependency that mirrors, in some respects, the West’s reliance on Chinese primary processing.

The Dutch chokepoint

If Spruce Pine illustrates vulnerability through geological accident, the Dutch company ASML demonstrates it through technological achievement. Based in Veldhoven, ASML holds a complete monopoly on extreme ultraviolet lithography machines – the 350 million euro devices capable of printing circuit patterns at scales measured in single-digit nanometres. No competitor has come close to matching its capabilities.

EUV lithography uses light with a wavelength of just 13.5 nanometres – roughly the length of five DNA strands – to etch transistor patterns onto silicon wafers. The technology required over 6.3 billion dollars in research and development across 17 years, drawing on work from DARPA, Bell Labs, IBM Research and the US national laboratories before being commercialised by a single European firm.

“ASML has a monopoly on the fabrication of EUV lithography machines, the most advanced type of lithography equipment needed to make every single advanced processor chip that we use today,” notes Chris Miller, assistant professor at Tufts University’s Fletcher School and author of Chip War. “The machines they produce, each one of them, are among the most complicated devices ever made.”

Yet ASML itself depends on more than 5,000 suppliers worldwide, with the largest concentration of critical components sourced from the United States. The company’s EUV light sources, acquired through its purchase of the American firm Cymer, exemplify this interdependence. The mirrors that focus EUV light – described by manufacturer Zeiss as “the most precise mirrors in the world” – are produced by locating imperfections and removing individual molecules using techniques such as ion beam figuring.

China’s uphill climb

Beijing has responded to Western export controls with unprecedented investment. A 47.5 billion dollar state-backed semiconductor fund announced in May 2024 exceeded the combined value of China’s two previous such funds. In the first half of 2024, Chinese firms spent more on chipmaking equipment than the US, Taiwan and South Korea combined.

The results have been mixed. China’s leading foundry, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), has achieved 7-nanometre chip production using older deep ultraviolet lithography equipment and a technique called multi-patterning. Analysis by Tokyo-based TechanaLye suggests Chinese manufacturing capability now trails industry leader TSMC by roughly three to five years – a significant improvement from a decade ago, but still a substantial gap in an industry where technological generations are measured in months.

More fundamentally, achieving semiconductor self-sufficiency requires catching up across more than 2,000 distinct technical subfields. Progress has been uneven: Chinese firms have made genuine advances in memory chips and mature-node manufacturing, but lag considerably in semiconductor manufacturing equipment, advanced packaging and the kind of ultra-pure materials processing that remains concentrated in the West and its allies.

“Anyone who tells you that the Chinese can overtake us in this industry is ridiculous,” argues one geopolitical expert who advises Western governments on technology policy. “But also anyone who tells you that we could do it ourselves is ridiculous. This is the most sophisticated supply chain system that humanity has ever created.”

The $20 trillion question

The fantasy of semiconductor autarky – whether American, Chinese or European – collides with economic and technical reality. Industry analysts estimate that establishing a fully domestic supply chain capable of producing leading-edge chips without any foreign inputs would require investment on the order of 20 trillion dollars and take approximately 40 years to complete.

The US CHIPS and Science Act allocated 52 billion dollars toward domestic manufacturing capacity – significant, but a fraction of what true self-sufficiency would demand. The European Union has set a goal of capturing 20 per cent of global semiconductor production by 2030, while Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have launched their own industrial policies.

What emerges is not a picture of clear winners and losers, but of mutual vulnerability. The United States and its allies control critical chokepoints in design software, manufacturing equipment, and ultra-pure materials. China dominates primary mineral processing and increasingly, mature-node chip production. Neither bloc can function without inputs controlled by the other.

The semiconductor industry’s structure – evolved over decades of globalisation and specialisation – reflects the economic logic of comparative advantage. Unravelling it in the name of national security imposes costs that policymakers are only beginning to comprehend. The question is no longer whether the chip supply chain is vulnerable, but whether the cure of fragmentation might prove worse than the disease of interdependence.

Back in Spruce Pine, the quartz mines have resumed operations. The crucibles continue to ship to Asia. And somewhere in a Taiwanese fab, silicon crystals grown in vessels made from Blue Ridge Mountain minerals are being sliced into the wafers that will power the next generation of artificial intelligence. The system holds – for now.

___

Sources: CSIS, Bloomberg Intelligence, ITIF, CNN, NPR, CNBC, ASML corporate disclosures, Sibelco corporate materials, Conway E. (2023) Material World, Miller C. (2022) Chip War

Read our full Report Disclaimer.

Report Disclaimer

This report is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or investment advice. The views expressed are those of Bretalon Ltd and are based on information believed to be reliable at the time of publication. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Recipients should conduct their own due diligence before making any decisions based on this material. For full terms, see our Report Disclaimer.