If you are reading this on a smartphone, you are holding a miracle of history in your hand. Not just a miracle of engineering, but a miracle of economics, geopolitics, and demographics. For the last thirty years, the global technology sector has surfed a perfect, rogue wave – a “Goldilocks” scenario of frictionless trade, bottomless labor pools in East Asia, and an ocean of cheap American capital.

We have grown accustomed to the idea that this wave is the permanent state of the ocean. We assume that technology will simply keep getting faster, cheaper, and more ubiquitous.

A rigorous analysis of current macro-trends suggests we may be wrong. The architecture supporting the modern tech ecosystem is cracking. However, there are two violently opposing views on what happens next. The first view is one of structural disintegration – a “Great Recalibration.” The second is a vision of exponential transcendence.

The Case for Collapse: The Myth of “Made in China”

To understand the potential crash, we must first dismantle a popular delusion: the idea that tech products are monolithic items “made” in one place.

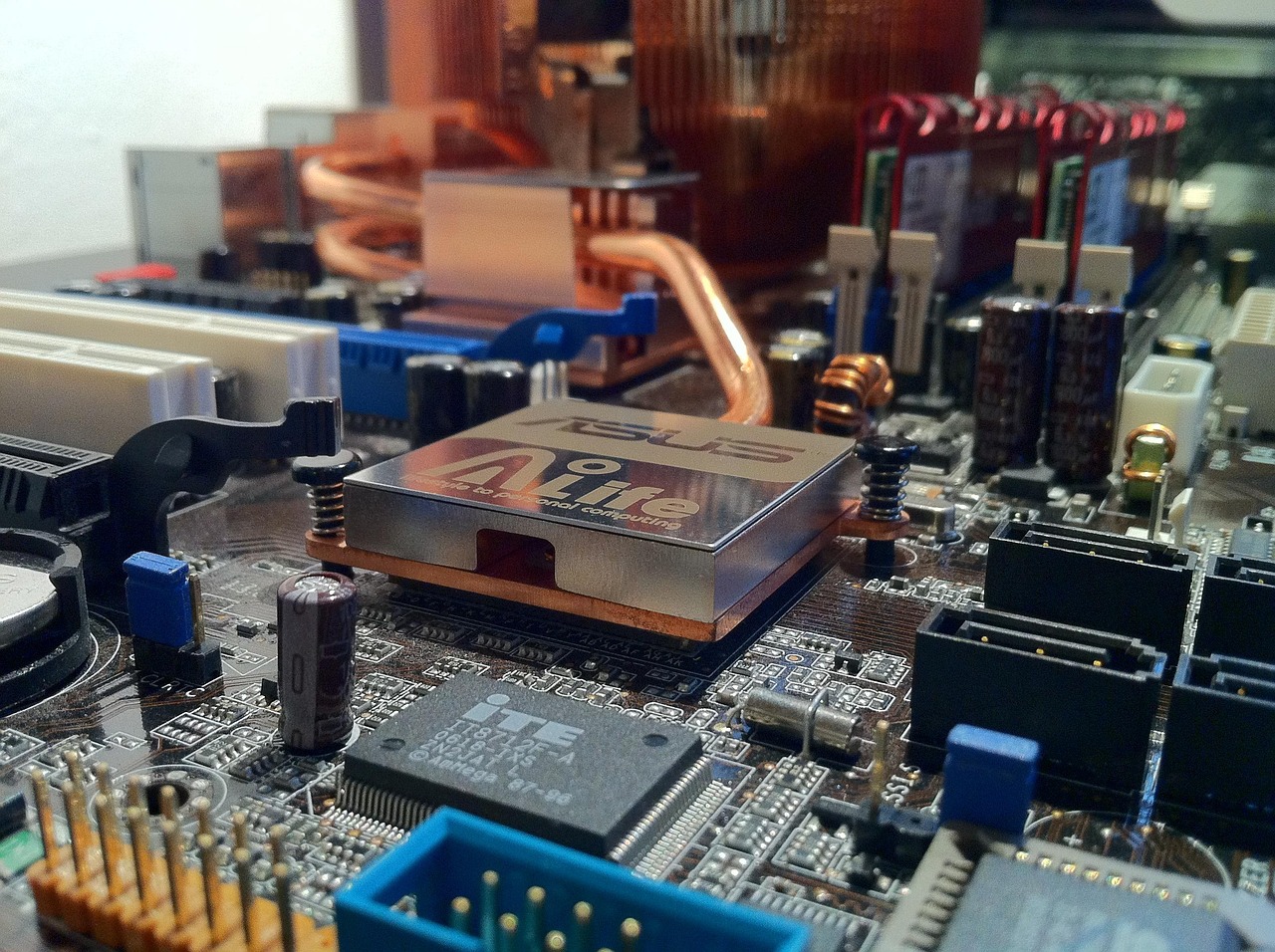

The reality is far more precarious. The tech sector relies on a supply chain of extreme granularity. A single high-end chip is not “manufactured”; it is birthed through a relay race involving 1,000 to 2,000 individual steps. This is a system of binary fragility. If one runner drops the baton, the race doesn’t slow down – it stops.

The research highlights that 85% of this capacity is locked in a highly specialized East Asian division of labor:

- South Korea holds the keys to memory (DRAM).

- Taiwan dominates the high-end logic and GPU market (the brains of AI).

- Japan controls the “chokepoint” chemicals like photo-resists.

- The Netherlands (via ASML) builds the EUV lithography machines—the only tools on Earth capable of etching modern chips.

This is not a redundant network; it is an interdependent house of cards. A disruption in Japanese chemical production doesn’t mean we switch to a backup supplier; it means the global production of high-end chips hits zero. The assumption that we can simply copy-paste this ecosystem to Arizona or Texas ignores decades of specialized industrial clustering.

The Tariff Paradox: How Protectionism Kills Innovation

In response to this fragility, American policy has pivoted toward protectionism. The logic seems sound: slap tariffs on foreign goods to force companies to “reshore” manufacturing to the United States.

However, when applied to the circular, hyper-complex world of tech, this policy is, to put it bluntly, borderline suicidal. Tech manufacturing involves intermediate goods crossing borders dozens of times to add incremental value. When the U.S. places tariffs on these inputs, it acts as a compounding tax on domestic manufacturers.

The result is a cruel irony known as “de-Americanization.” Multinational corporations aren’t moving the upstream manufacturing to the U.S. because the capital costs are too high. Instead, to dodge the tariff wall, they are moving the remaining downstream value-add steps out of the U.S., relocating to Vietnam or Mexico.

The End of the Free Money Era

Even if we could solve the manufacturing puzzle, we face a harder problem: the fuel is running out.

The tech boom of 2005–2020, the era that gave us Uber, Airbnb, and the explosion of SaaS, was underwritten by historically cheap capital. This was driven by Baby Boomers in their peak earning years creating a glut of loanable funds.

That tide is going out. The Boomers have retired. Retirees do not save; they liquidate. As they pull trillions out of the markets, the cost of capital skyrockets. We have already seen a 4x to 5x increase in the cost of money compared to the zero-interest years. For a sector that relies on moonshots with profits delayed by a decade, this is catastrophic.

The Graying of the Valley

Finally, there is the human element. The engine of Silicon Valley was powered by a specific demographic cohort: Millennials. From 2005 to 2015, this group was young, risk-tolerant, and willing to embrace “hustle culture.”

Those Millennials are now pushing 40. They are prioritizing stability. Compounding this is a demographic collapse in the manufacturing hubs. East Asia is dying. South Korea’s fertility rate is under 0.8; China’s workforce is shrinking. We are facing a future where we have the blueprints for the technology, but lack the skilled hands required to build it and the young minds required to dream it up.

The Counter-Wager: The Age of Infinite Abundance

However, there is a counter-narrative, a vision espoused by figures like Elon Musk, Marc Andreessen, and the leaders of the AI revolution, that suggests the “unraveling” is merely the friction of a rocket escaping gravity. They argue that the pessimists are engaging in linear thinking in an exponential world.

The core of this “Abundance Thesis” is that technology is about to solve the very constraints that the pessimists fear.

Solving the Demographic Collapse: While the pessimists worry about shrinking labor pools in China and the US, the techno-optimists argue that human labor is about to become optional. The rapid advancement of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) and humanoid robotics (such as Tesla’s Optimus) promises to decouple economic output from human headcount. If a $20,000 robot can work 20 hours a day, the “fertility crisis” becomes irrelevant. We are not running out of workers; we are simply transitioning from biological labor to silicon labor. In this view, a shrinking population is not a crisis, but a perfectly timed evolution toward a post-labor economy.

The Deflationary Tsunami: The pessimist worries about the cost of capital and inflation. The optimist retorts that technology is the ultimate deflationary force. AI intelligence is currently trending toward a marginal cost of zero. When intelligence—the most valuable commodity in history—becomes free, the cost of designing chips, optimizing logistics, and discovering new materials collapses.

Musk and others envision a future of “Energy Abundance” via solar and batteries, and eventually fusion. When you combine near-infinite intelligence with near-infinite energy, the cost of goods crashes. It won’t matter if interest rates are 5% or 10% if the cost to manufacture a car or build a home drops by 80% due to automated supply chains and materials science breakthroughs.

Resilience through First Principles: Finally, the “fragile supply chain” argument ignores the revolution in manufacturing itself. The old world relies on the distributed, granular supply chain described above. The new world, championed by companies like SpaceX, relies on extreme vertical integration and “first principles” engineering. Instead of relying on a web of 2,000 suppliers, the new industrial tech giants build in-house, use massive simplification (like the Giga Press in automotive), and utilize 3D printing for rapid prototyping.

The techno-optimist does not see a crumbling house of cards; they see the chrysalis breaking. They believe we are on the verge of a “Singularity” – a point where technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, resulting in unfathomable changes to human civilization. In this scenario, the current struggles are not the end of the Golden Age, but the birth pangs of an Age of Abundance where scarcity is a memory.

The New Normal: Scarcity or Singularity?

We stand at a crossroads between these two realities.

The data on supply chains, demographics, and interest rates points toward the “Great Unraveling.” If these macro-forces prevail, the future of tech will be characterized by scarcity, slower product cycles, significantly higher costs, and a focus on resilience over efficiency.

However, if the “Abundance Thesis” holds true, these macro-forces will be swept away by a tsunami of automation and energy breakthroughs. The party isn’t winding down; it is mutating into something unrecognizable.

Business leaders and investors must now place their bets: Are we heading for a long winter of retrenchment, or are we standing on the launchpad of the greatest upward leap in human history?

Read our full Report Disclaimer.

Report Disclaimer

This report is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or investment advice. The views expressed are those of Bretalon Ltd and are based on information believed to be reliable at the time of publication. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Recipients should conduct their own due diligence before making any decisions based on this material. For full terms, see our Report Disclaimer.